This article is the second of a series about knowledge acceleration and fragmentation, after Knowledge Flood and Change Acceleration.

Globalization of knowledge creation

For the first time in 2012, Chinese residents accounted for the largest number of patents filed throughout the world (World Intellectual Property Indicators, December 2013).

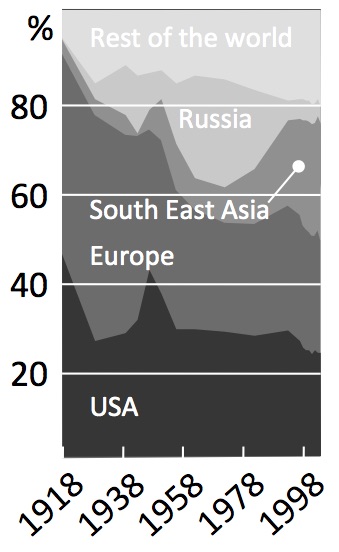

The Chemical Abstracts Service data (the same data that in the previous article) were analyzed with regard to the geographical origins of the authors. The resulting geographic distribution of each year’s publications is shown in the figure.

It appears that the growth deficit observed in the figure during the 1980s was due to the collapse of the USSR and the associated countries pulling out of the knowledge-creation race, presumably temporarily. The most significant long-term trend is the globalization of knowledge creation. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Europe and the United States were dominant, generating more than 90% of scientific publications; by the turn of the twenty-first century, Asia and the rest of the world accounted for about 50% of scientific publications. The most recent data show that emerging countries, such as China, India, and Brazil, now account for a growing share of knowledge creation.

In these so-called emerging countries, there an increasing number of engineers and researchers producing knowledge. Never in history have so many people worked in research laboratories. Is the rate of knowledge creation increasing simply because there are more educated people to contribute to the effort? It is certainly one of the drivers, but many thinkers are pointing at even more basic roots for acceleration of knowledge creation.

Exponential knowledge growth

Knowledge begets knowledge as money bears interest (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Parasite, 1885)

The above quote from the father of Sherlock Holmes provides a simple, basic explanation for accelerated knowledge growth. Indeed, new knowledge is built on an existing base of knowledge. If one assumes some proportionality between initial and resulting knowledge created during a given period, this is enough to lead to exponential growth. Derek J. de Solla Price, the father of scientometrics proposed optimized ways of measuring the production of scientific knowledge, and his conclusions leaned toward exponential growth. Other authors elaborated on his work; one refinement was the introduction of an additional parameter, the quality of the new knowledge.

Measuring the growth of knowledge is difficult, particular over a long period of time. The definitions of quality and newness have changed over the years. In the first millennium, manuscripts were a means of propagating knowledge by reproduction rather than of publishing new contributions. Recent electronic publications are also difficult measure in a sufficiently rigorous and consistent manner.

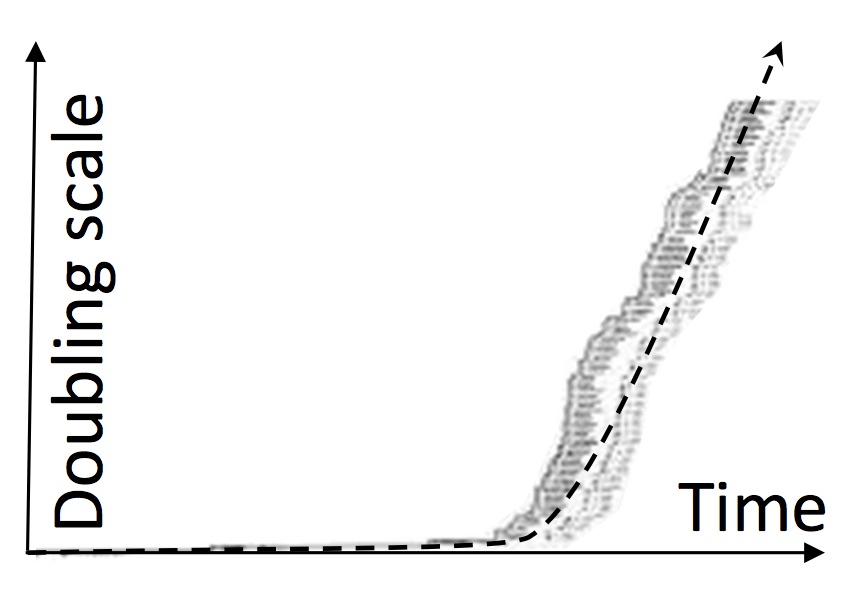

Buckminster Fuller’s data, shown here in gray, displays his estimate for the doubling rate for accumulated knowledge. The time scale begins with Johannes Gutenberg, who lived from approximately 1398 to 1468, and ends in the 1970s. Doubling scale is the inverse of the time required to see the volume of accumulated knowledge double. As emphasized by the black dashed arrow, the doubling rate increased dramatically during the twentieth century.

The measurement challenge has not stopped some daring authors, however. Many authors claim that knowledge creation is accelerating at a rate even faster than an exponential one. Mere exponential growth would imply that accumulated knowledge doubles at a consistent pace. One of the first people to analyze the growth of knowledge was Buckminster Fuller[1]. He estimated the historical variation in the doubling time of knowledge. Fuller used printed materials as a proxy for knowledge; as shown in the figure, he found that although knowledge had doubled approximately every century up until the eighteenth century, then sometime during the nineteenth century its growth rate accelerated dramatically.

Fuller’s analysis demonstrated a recent acceleration in knowledge growth since the nineteenth century. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s simple explanation does not provide a reason for knowledge “interest” to be generated at a faster-than-exponential rate. This acceleration, specific to the era since the Industrial Revolution, may have multiple root causes. We have already mentioned the increasing number of people working of knowledge creation, a result of population growth combined with an increasing proportion of educated people. The faster communication system, which speeds up feedback loops among thinkers and thus limits losses of time and efficiency associated with redundancy, is another cause. Some authors are exploring additional causes. According to Gerald S. Hawkins, progress generally proceeds via mindsteps, dramatic and irreversible changes to paradigms or world views. Indeed, humankind has achieved spectacular advances in the way it thinks as a collective body, introducing new mindsteps such as speech, writing, printing, symbolic calculus, computers, data mining. Hawkins has further explained that key mindsteps are appearing at an accelerated rate and humankind is indeed learning, discovering, and inventing faster now, as such mindsteps are incorporated into its collective mind.

[1] Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) was a famous thinker and architect. He designed the bucky ball, a geodesic structure that was later discovered to be similar to fullerene molecules.

***

This article was initially published in the book Innovation Intelligence (2015). It is the first section of the fourth chapter.